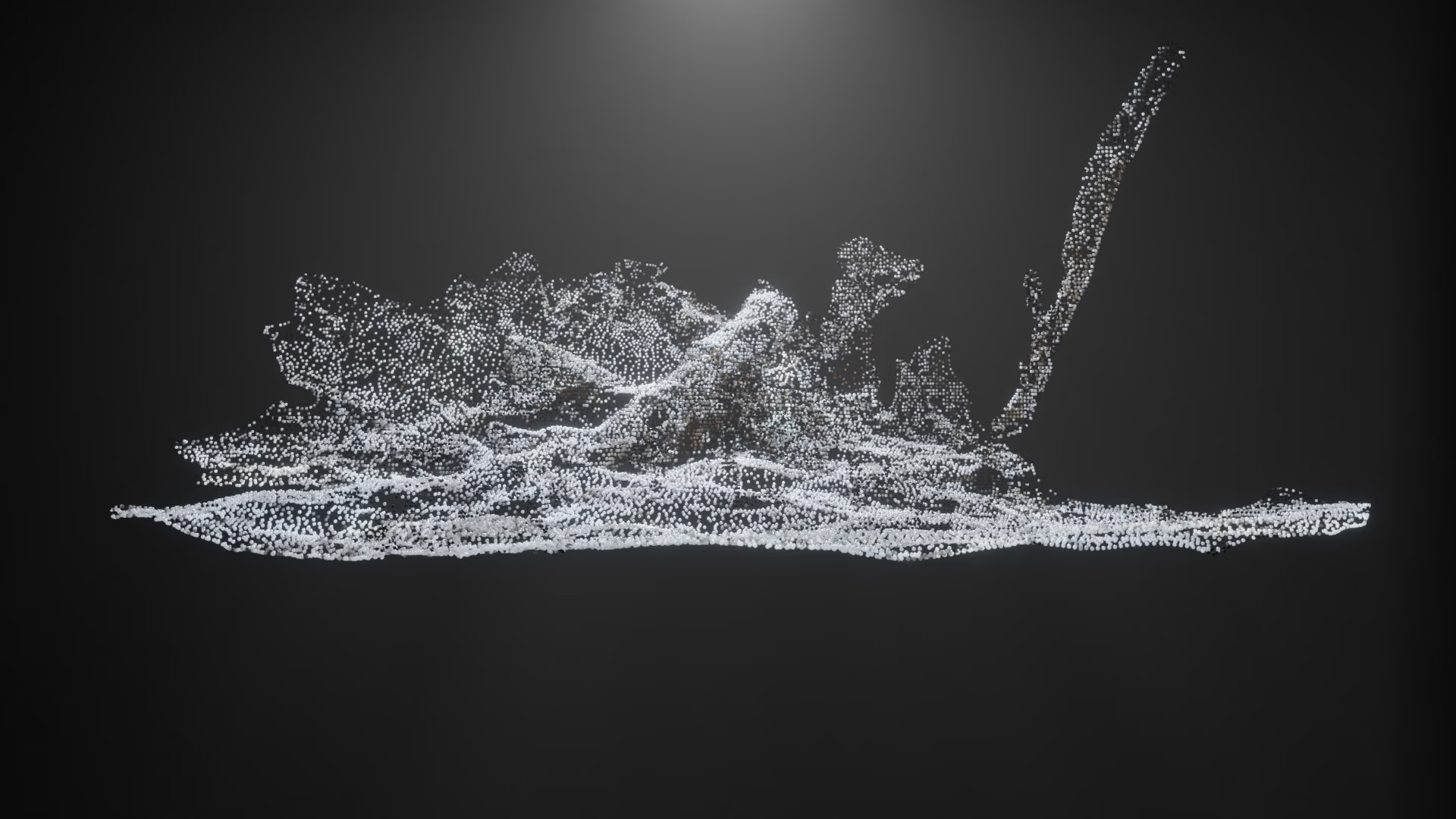

Manipulated LiDAR data, field-recorded audio, botanical samples, mud, melted snow.

What is the role of embodied relationship in knowing the world around us? Mechanistic reductionism, a cornerstone of modern science since the Enlightenment period, would have us believe that presence and relationality are, at best, hindrances: only with a clinical, objective breaking down of the world into its constitutive parts might we hope to be blessed with the fruits of true understanding; in ideal conditions, the enquiring mind, the enquiring body, is effectively erased.

Known Place takes the scientific method to task, dissecting a chosen site in Toronto’s Don Valley and re-contextualizing its constituents to ask: how deeply can we truly know our world within this orthodoxy of reductive quantification and bodily effacement? What wisdom, what fresh threads of questioning, are occluded by its walls? What is the felt difference between a representation and the “real thing?” What might be gained from revisiting the foundations of scientific methodology, particularly in the face of a mounting ecological crisis that invites us to step into radically new perspectives?

A collection of numbered jars containing botanical samples, mud, melted snow, is presented in front of a projected LiDAR visualization of the site. Numbers positioned within the visualization indicate the locations at which each respective sample was retrieved. Field recorded audio can be heard through a pair of headphones. This is a clinical cataloguing of a real place. But could it truly be said that these parts, severed of their relationships, stripped of their sensate continuity, offer a true representation of this place? Or has something essential been lost in the act of severing?

With growing awareness of the observer effect and the replication crisis, Known Place explores our inextricable entanglement with(in) an ever-changing world, pushing back against the nature/culture, subject/object dichotomies that have shaped the sciences for centuries. Of what do we lose sight when we break apart complex systems and neglect to put them back together again? And how might we restructure our models and methods of enquiry to be as dynamic and adaptable as the living world around us?